Nombre:

Catedral de Liverpool

Otro: Catedral anglicana de Liverpool

Localización:

View Larger Map

Tipo: Edificios Religiosos

Categoría:

Foto:

Voto:

Continente: Europa

País: Reino Unido

Localización:

Año: 1904-1978

Estado: Terminado

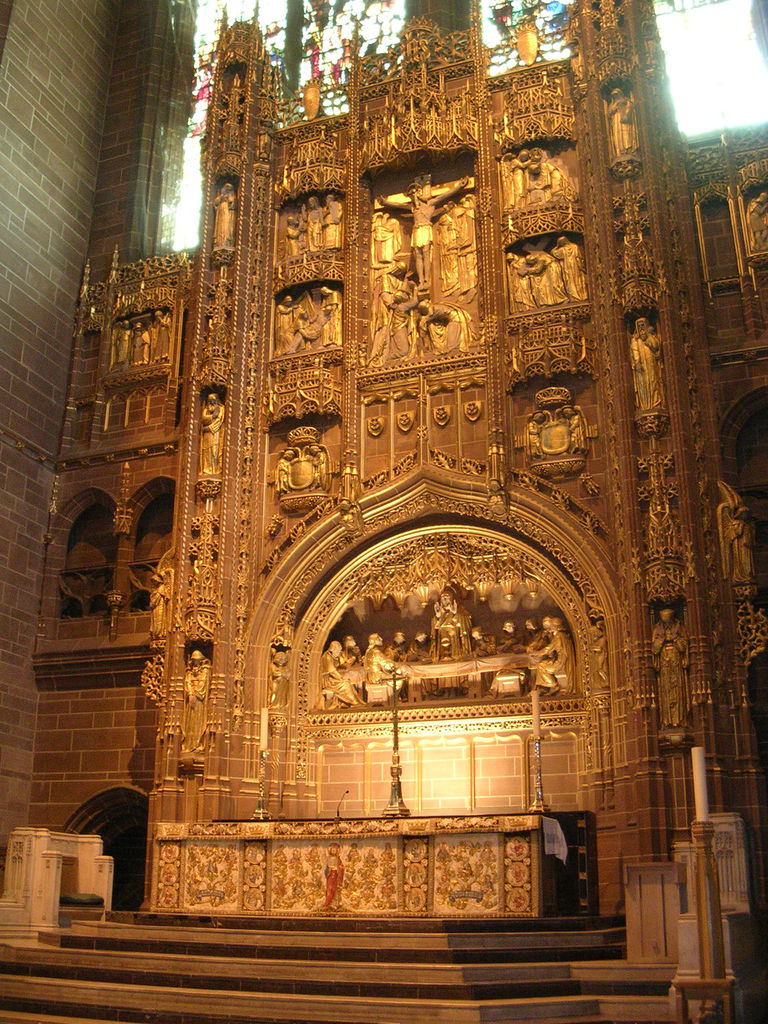

Descripción:La catedral anglicana de Liverpool (oficialmente Church of Christ Cathedral y conocida en inglés como Liverpool Cathedral o Liverpool Anglican Cathedral), diseñada por sir Giles Gilbert Scott, fue iniciada en 1904 pero no se terminó hasta 1978, dieciocho años después de la muerte de Scott. El enorme edificio está construido en arenisca roja, en un austero estilo gótico del siglo XX que crea una atmósfera de espacio místico propia para el recogimiento.

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catedral_de_Liverpool

Liverpool Cathedral is the Church of England cathedral of the Diocese of Liverpool, built on St James's Mount in Liverpool and is the seat of the Bishop of Liverpool. Its official name is the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool but it is dedicated to Christ and the Blessed Virgin. The total external length of the building, including the Lady Chapel, is 189 metres (620 ft) making it the second longest cathedral in the world; its internal length is 146 metres (479 ft). In terms of overall volume, Liverpool Cathedral ranks as the fifth-largest cathedral in the world[1] and contests the title of largest Anglican church building alongside the incomplete Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City.[2] With a height of 100.8 metres (331 ft) it is also one of the world's tallest non-spired church buildings and the third-tallest structure in the city of Liverpool.

The Anglican cathedral is one of two in the city. The other, the Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Liverpool, is situated approximately half a mile to the north. The cathedrals are linked by Hope Street, which takes its name from William Hope, a local merchant whose house stood on the site now occupied by the Philharmonic Hall, and was named long before either cathedral was built.

History

Background

John Charles Ryle was installed as the first Bishop of Liverpool in 1880, but the new diocese had no cathedral, merely a "pro-cathedral", the parish church of St Peter's, Church Street. St Peter's was unsatisfactory; it was too small for major church events, and moreover was, in the words of the Rector of Liverpool, "ugly & hideous".[3] In 1885 an Act of Parliament authorised the building of a cathedral on the site of the existing St John's Church, adjacent to St George's Hall.[4] A competition was held for the design, and won by Sir William Emerson. The site proved unsuitable for the erection of a building on the scale proposed, and the scheme was abandoned.[4]

In 1900 Francis Chavasse succeeded Ryle as bishop, and immediately revived the project to build a cathedral.[5] There was some opposition from among members of Chavasse's diocesan clergy, who maintained that there was no need for an expensive new cathedral. The architectural historian John Thomas argues that this reflected "a measure of factional strife between Liverpool Anglicanism's very Evangelical or Low Church tradition, and other forces detectable within the religious complexion of the new diocese."[6] Chavasse, though himself an Evangelical, regarded the building of a great church as "a visible witness to God in the midst of a great city".[6] He pressed ahead, and appointed a committee under Sir William Forwood to consider all possible sites. The St John's site being ruled out, Forwood's committee identified four locations: St Peter's and St Luke's, which were, like St John's, found to be too restricted; a triangular site at the junction of London Road and Monument Place;[n 1] and St James's Mount.[7] There was considerable debate about the competing merits of the two possible sites, and Forwood's committee was inclined to favour the London Road triangle. However, the cost of acquiring it was too great, and the St James's Mount site was recommended.[7] A historian of the cathedral, Vere Cotton, wrote in 1964:

Looking back after an interval of sixty years, it is difficult to realise that any other decision was even possible. With the exception of Durham, no English cathedral is so well placed to be seen to advantage both from a distance and from its immediate vicinity. That such a site, convenient to yet withdrawn from the centre of the city … dominating the city and clearly visible from the river, should have been available is not the least of the many strokes of good fortune which have marked the history of the Cathedral.[7]

Fund-raising began, and new enabling legislation was passed by Parliament. The Liverpool Cathedral Act 1902 authorised the purchase of the site and the building of a cathedral, with the proviso that as soon as any part of it opened for public worship, St Peter's Church should be demolished and its site sold to provide the endowment of the new cathedral's chapter. St Peter's place as parish church of Liverpool would be taken by the existing church of St Nicholas near the Pier Head.[7]

1901 competition

In late 1901, two well-known architects were appointed as assessors for an open competition for architects wishing to be considered for the design of the cathedral.[8] G. F. Bodley was a leading exponent of the Gothic revival style, and a former pupil and relative by marriage of Sir George Gilbert Scott.[9] R. Norman Shaw was an eclectic architect, having begun in the Gothic style, and later favouring what his biographer Andrew Saint calls "full-blooded classical or imperial architecture".[10]

Giles Gilbert Scott's winning design, with twin towers

Architects were invited by public advertisement to submit portfolios of their work for consideration by Bodley and Shaw. From these, the two assessors selected a first shortlist of architects to be invited to prepare drawings for the new building. It was stipulated that the designs were to be in the Gothic style.[11] Robert Gladstone, a member of the committee to which the assessors were to report said, "There could be no question that Gothic architecture produced a more devotional effect upon the mind than any other which human skill had invented."[12] This condition caused controversy. Reginald Blomfield and others protested at the insistence on a Gothic style, a "worn-out flirtation in antiquarianism, now relegated to the limbo of art delusions."[13] An editorial in The Times observed, "To impose a preliminary restriction is unwise and impolitic … the committee must not hamper itself at starting with a condition which is certain to exclude many of the best men."[14] Eventually it was agreed that the assessors would also consider "designs of a Renaissance or classical character".[15]

For architects, the competition was an important event; not only was it for one of the largest building projects of its time, but it was only the third opportunity to build an Anglican cathedral in England since the Reformation in the 16th century (St Paul's Cathedral being the first, rebuilt from scratch after the Great Fire of London in 1666, and Truro Cathedral being the second, begun in the 19th century).[15] The competition attracted 103 entries,[15] from architects including Temple Moore, Charles Rennie Mackintosh[16] and Charles Reilly.[17]

In 1903, the assessors recommended a proposal submitted by the 22-year-old Giles Gilbert Scott, who was still an articled pupil working in Temple Moore's practice,[18] and had no existing buildings to his credit. He told the assessors that so far his only major work had been to design a pipe-rack.[19] The choice of winner was even more contentious with the cathedral committee when it was discovered that Scott was a Roman Catholic,[n 2] but the decision stood.[18]

Scott's first design

Although young, Scott was steeped in ecclesiastical design and well versed in the Gothic revival style, his grandfather, George Gilbert Scott, and father George Gilbert Scott, Jr. having designed numerous churches.[20] George Bradbury, the surveyor to the cathedral committee, reported, "Mr. Scott seems to have inherited the architectural genius so marked in the Scott family for the last three or four generations ... He is very pleasant, agreeable, enthusiastic, tall, and looks considerably older than he actually is."[6] Appearances notwithstanding, Scott's inexperience prompted the cathedral committee to appoint Bodley to oversee the detailed architectural design and building work. Work began without delay. The foundation stone was laid by King Edward VII in 1904.[3]

Cotton observes that it was generous of Bodley to enter into a working relationship with a young and untried student.[21] Bodley had been a close friend of Scott's father, but his collaboration with the young Scott was fractious, especially after Bodley accepted commissions to design two cathedrals in the U.S.,[n 3] necessitating frequent absences from Liverpool.[18] Scott complained that this "has made the working partnership agreement more of a farce than ever, and to tell the truth my patience with the existing state of affairs is about exhausted".[18] Scott was on the point of resigning when Bodley died suddenly in 1907, leaving him in charge.[22] The cathedral committee appointed Scott sole architect, and though it reserved the right to appoint another co-architect, it never seriously considered doing so.[6]

Scott's 1910 redesign

Scott's 1910 redesign, with central tower

In 1909, free of Bodley and growing in confidence, Scott submitted an entirely new design for the main body of the cathedral.[23] His original design had two towers at the west end[n 4] and a single transept; the revised plan called for a single central tower 85.344 metres (280.00 ft) high, topped with a lantern and flanked by twin transepts.[25][n 5] The cathedral committee, shaken by such radical changes to the design they had approved, asked Scott to work his ideas out in fine detail and submit them for consideration.[23] He worked on the plans for more than a year, and in November 1910, the committee approved them.[23] In addition to the change in the exterior, Scott's new plans provided more interior space.[27] At the same time Scott modified the decorative style, losing much of the Gothic detailing and introducing a more modern, monumental style.[28]

The Lady Chapel (originally intended to be called the Morning Chapel),[6] the first part of the building to be completed, was consecrated in 1910 by Bishop Chavasse in the presence of two archbishops and 24 other bishops.[29] The date, 29 June – St Peter's Day, was chosen to honour the pro-cathedral, now due to be demolished.[30] The Manchester Guardian described the ceremony:

The Bishop of Liverpool knocked on the door with his pastoral staff, saying in a loud voice, "Open ye the gates." The doors having been flung open, the Earl of Derby, resplendent in the golden robes of the Chancellor of Liverpool University, presented Dr. Chavasse with the petition for consecration. … The Archbishop of York, whose cross was carried before him and who was followed by two train-bearers clad in scarlet cassocks, was conducted to the sedilla, and the rest of the bishops, with the exception of Dr. Chavasse, who knelt before his episcopal chair in the sanctuary, found accommodation in the choir stalls.[31]

The richness of the décor of the Lady Chapel may have dismayed some of Liverpool's Evangelical clergy. Thomas suggests that they were confronted with "a feminized building which lacked reference to the 'manly' and 'muscular Christian' thinking which had emerged in reaction to the earlier feminization of religion."[6] He adds that the building would have seemed to many to be designed for Anglo-Catholic worship.[6]

Second phase

Work was severely limited during the First World War, with a shortage of manpower, materials and donations.[32] By 1920, the workforce had been brought back up to strength and the stone quarries at Woolton, source of the red sandstone for most of the building, reopened.[32] The first section of the main body of the cathedral was complete by 1924. It comprised the chancel, an ambulatory, chapter house and vestries.[33] The section was closed with a temporary wall, and on 19 July 1924, the 20th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone, the cathedral was consecrated in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary, and bishops and archbishops from round the globe.[32]

Major works ceased for a year while Scott once again revised his plans for the next section of the building: the tower, the under-tower and the central transept.[34] The tower in his final design was higher and narrower than his 1910 conception.[35]

From July 1925 work continued steadily, and it was hoped to complete the whole section by 1940.[36] The outbreak of the World War II in 1939 caused similar problems to those of the earlier war. The workforce dwindled from 266 to 35. Moreover, the building was damaged by German bombs.[37] Despite these vicissitudes, the central section was complete enough by July 1941 to be handed over to the Dean and Chapter. Scott laid the last stone of the last pinnacle on the tower on 20 February 1942.[38] No further major works were undertaken during the rest of the war. Scott produced his plans for the nave in 1942, but work on it did not begin until 1948.[39] The bomb damage, particularly to the Lady Chapel, was not fully repaired until 1955.[40]

Completion

Scott died in 1960. The first bay of the nave was then nearly complete, and was handed over to the Dean and Chapter in April 1961. Scott was succeeded as architect by Frederick Thomas.[41] Thomas, who had worked with Scott for many years, drew up a new design for the west front of the cathedral. The Guardian commented, "It was an inflation beater, but totally in keeping with the spirit of the earlier work, and its crowning glory is the Benedicite Window designed by Carl Edwards and covering 1,600 sq. ft."[42]

The completion of the building was marked by a service of thanksgiving and dedication in October 1978, attended by Queen Elizabeth II. In the spirit of ecumenism that had been fostered in Liverpool, the Roman Catholic Archbishop Derek Worlock played a major part in the ceremony.[43]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liverpool_Cathedral

La construcción de la Catedral de Liverpool

Publicado por Jose Manuel Vargas

La Iglesia Catedral de Cristo en Liverpool, obra maestra de Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, está construida sobre el monte Saint James y puede verse desde varios kilómetros a la redonda, algo así como un testimonio visible de la presencia de Dios en medio de la ciudad.

Después de ponerse a concurso su diseño, el elegido fue el de un joven de apenas 22 años. En 1904 el rey Eduardo VII puso la primera piedra de su construcción en presencia de más de 7000 personas. Dicha construcción comenzó en el extremo oriental, y por medio de una sucesión de paredes, el edificio se realizó por completo.

La Capilla de la Señora fue consagrada el día de San Pedro de 1910, y la parte principal de la Catedral, incluyendo el Santuario, la Cámara, el Coro y el transepto, fueron consagrados el 19 de julio de 1924, 20 años después de la colocación de la primera piedra.

Los primeros servicios religiosos se llevaron a cabo en los oscuros días de la guerra de 1940. La ciudad de Liverpool fue duramente bombardeada, pero milagrosamente la Catedral sólo sufrió daños menores, y el último tramo de su torre se construyó en 1942. Los trabajos se reanudaron después de la guerra, y el Puente se completó en 1961.

A pesar de todo los esfuerzos, por fin la Catedral pudo concluirse en 1978, asistiendo la reina Isabel II para conmemorar el fin de los trabajos de la Catedral más grande de Inglaterra. La Catedral ofrece sus servicios a toda la población de Liverpool.

Sin duda alguna se ha convertido en uno de los elementos más espectaculares de la ciudad. Su sobria estructura puede verse desde mucho más allá, y todas las personas que quieran acercarse a Liverpool no pueden por menos que visitar el templo. Os impresionará a simple vista, incluso más desde la distancia que en su interior.

http://sobreinglaterra.com/2009/01/09/la-construccion-de-la-catedral-de-liverpool/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/oneterry/sets/72157614937613489/with/3592052495/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jinxsi/sets/72157627600253144/with/6116845607/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/allancarruthers/sets/72157625033389918/with/5024448942/

La catedral de Liverpool, al son de 'Imagine'

Uno de los campanarios más altos del mundo repicará la canción de John Lennon en su ciudad natal

EFE Londres 27 FEB 2009 - 17:51 CET

Las campanas de la catedral anglicana de Liverpool interpretarán este año la famosa canción Imagine de John Lennon, definida por su propio autor e hijo pródigo de la ciudad como un "himno antirreligioso".

Los responsables de la catedral, que tiene uno de los campanarios más altos del mundo, han considerado detenidamente "la sensibilidad" de la letra y han decidido que su capacidad de atraer a las masas supera su potencial para la ofensa.

Un portavoz catedralicio ha explicado que la iniciativa de interpretar el tema mediante repique de campanas partió de los organizadores del festival cultural Futuresonic, que se celebrará del 13 al 16 de mayo en Manchester y Liverpool.

Cuando Drew Hemment, fundadora del festival en 1995, tuvo la idea de tocar Imagine con un fondo de campanas pensó que ello debería hacerse en Liverpool, la ciudad natal de Lennon y del resto de los Beatles.

La conocida canción, escrita en 1971 y descrita por Lennon como "antirreligiosa, anticonvencional y anticapitalista", llama con su letra a imaginar que no existe ni el cielo, ni el infierno, ni la propiedad privada. Así seríamos todo, según Lennon, mucho más felices.

"La actuación propuesta inspirará a la reflexión ya que llama a la paz en un mundo roto y atormentado", ha expresado un portavoz de esta catedral anglicana, que tiene un impresionante campanario de más de cien metros de altura, formado por trece campanas que rodean a una central llamada El Gran Jorge, que pesa más de catorce toneladas y se puede oír a kilómetros a distancia.

Hemment ha señalado que la fusión de fe y laicismo que representa el concierto que se interpretará en el templo "refleja el tradicional carácter tolerante y valiente" de la ciudad.

http://elpais.com/elpais/2009/02/27/actualidad/1235720932_850215.html

Vídeo:

Web recomendada: http://www.liverpoolcathedral.org.uk/

Contador: 7663

Inserción: 2012-08-01 14:04:21

Lugares a visitar en un radio de 100 km (en línea recta)

Mapa de los lugares a 100 km (en línea recta)

Mostrando Registros desde el 1 hasta el 0 de un total de 0

Visitas |

Más visitados Basílica de San Marcos 149078 Catedral de Notre Dame (París) 137703 Torre de Pisa 128213 Monte Saint-Michel 97343 Presa de las Tres Gargantas 73674 |

Incorporaciones |

Comentarios Arq. Jaime Fuentes Flores Torres Obispado EXTRAORDINARIO . FELICIDADES . Un Cordial saludo Directivos y Personal de ... hazola Cúpula de la Roca gracias me... gera Buenos Aires las mejores fotos de la mejor ciudad del... Daniel M. - BRASIL San Francisco ... PEQUE Presa Chicoasén SERA QUE ALGUIEN ME PUEDE DAR MAS INFORMACIÓN DE ESTE PROYECTO ESTUDIO EN LA UNACH Y ES PARA UN... |

Tweet

Tweet